Marianne Hauser. Prince Ishmael. New York. Stein & Day. 1963. 316 pages.

Reprinted, Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Classics Series, 1991.

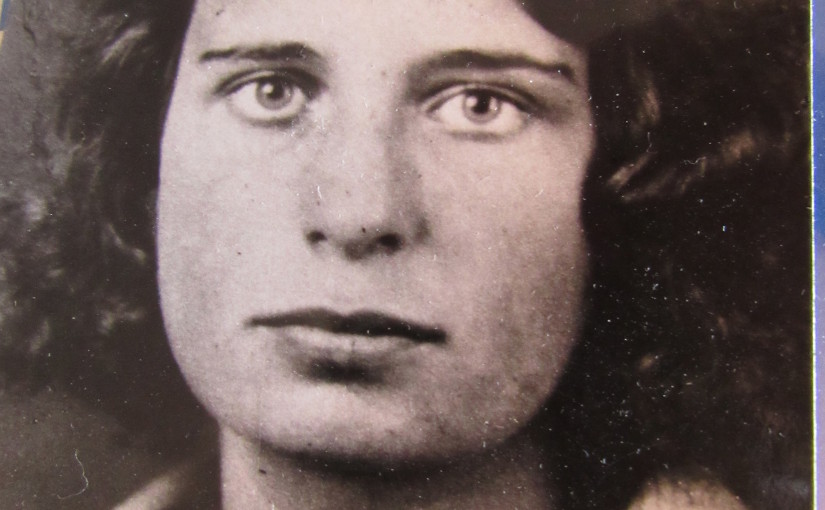

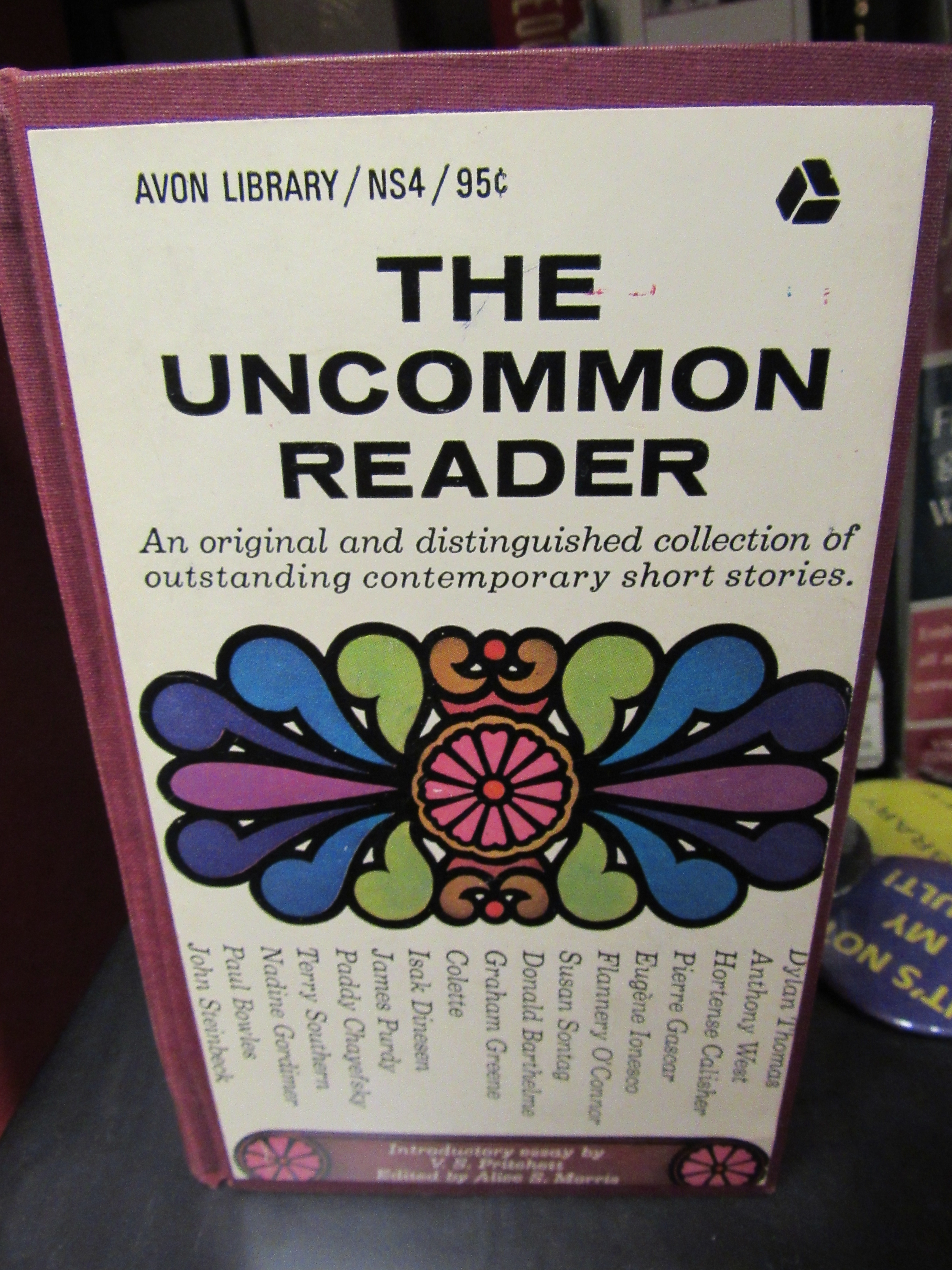

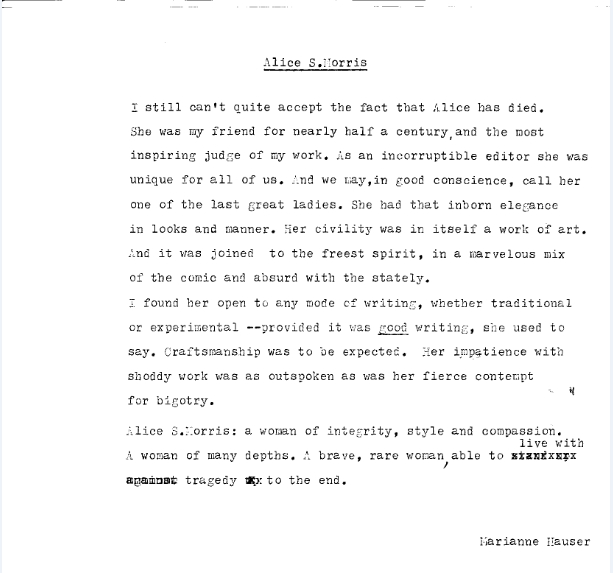

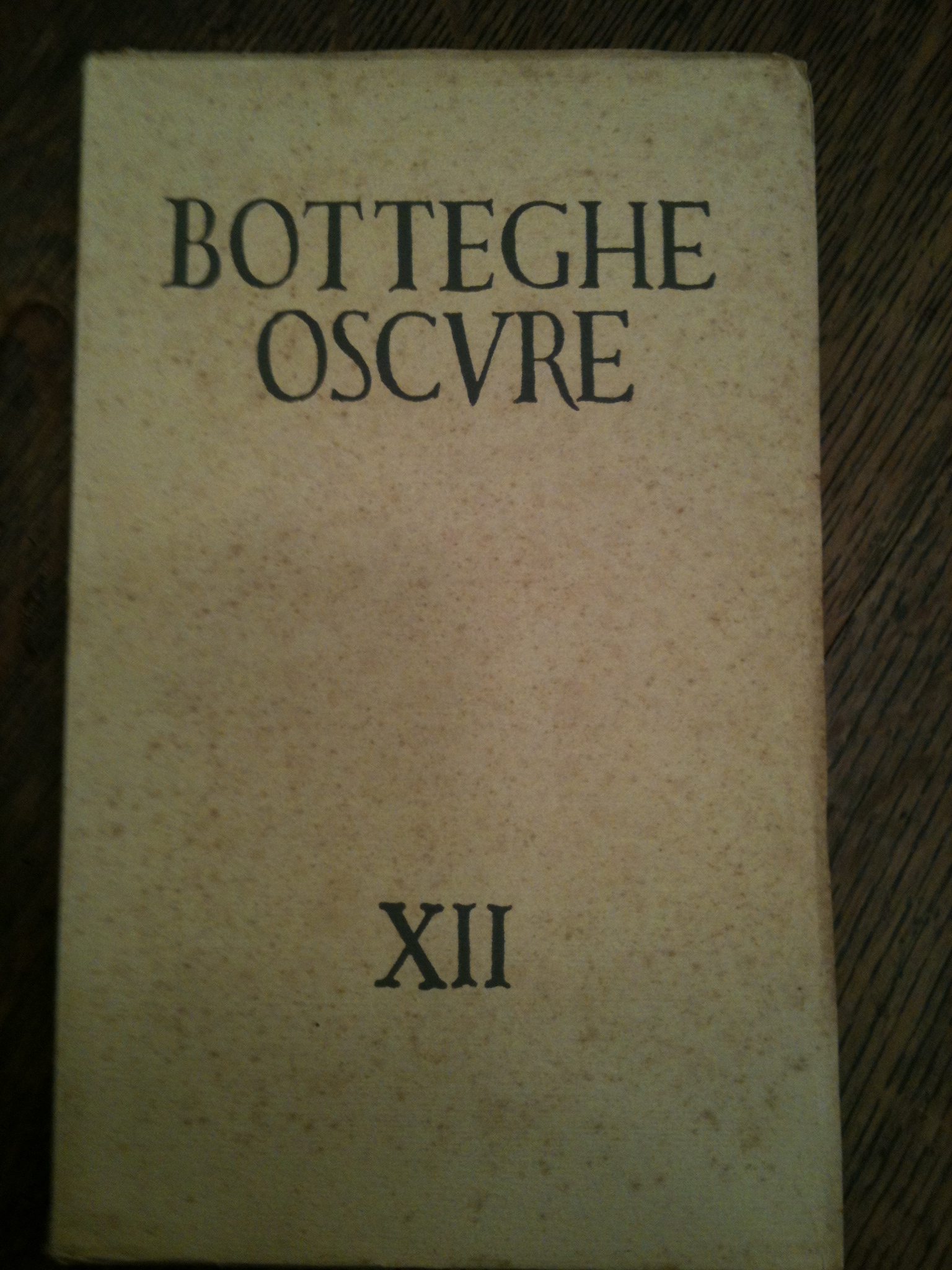

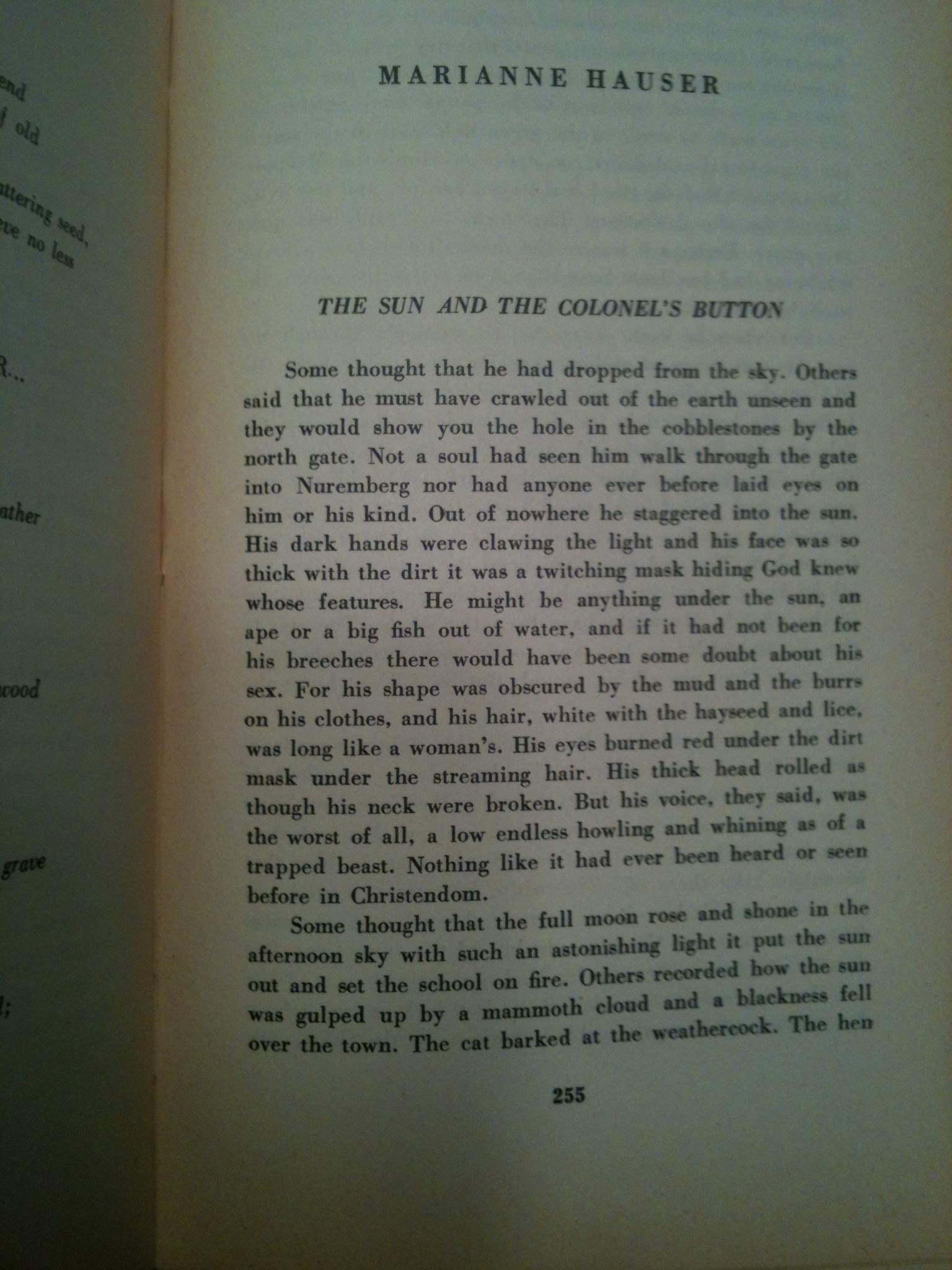

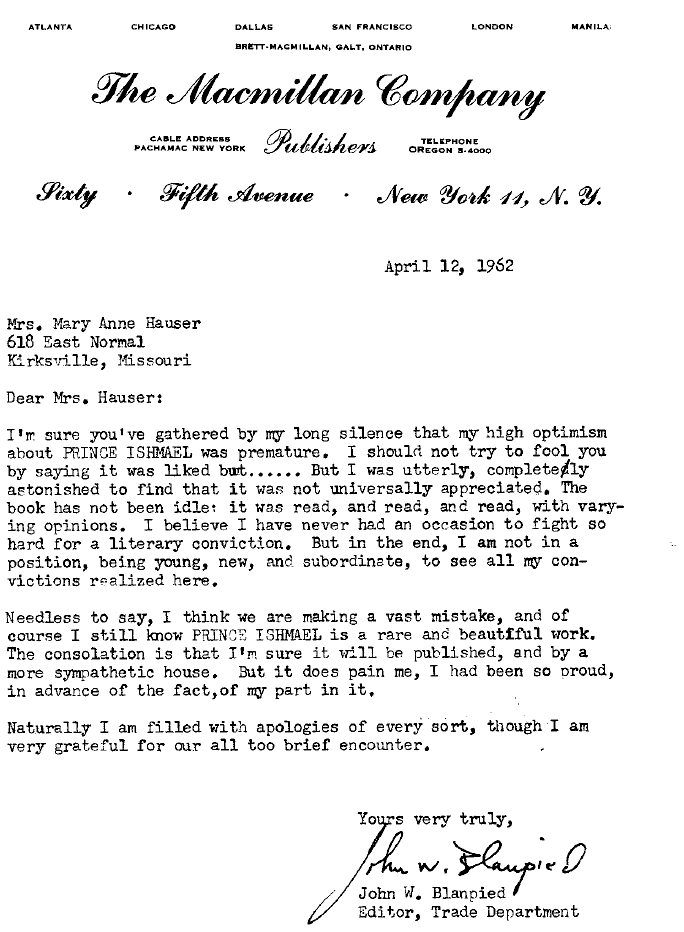

PRINCE ISHMAEL is the work Marianne Hauser spent decades writing, the book that was in her mind before all others. Her uncle, Ludwig Hauser, gave her a two volume dossier on Kaspar Hauser, the legendary German foundling (no relation, but of course there had to be, and she later said that she WAS Kaspar) when she was a young teen. It was the book that was supposed to be her big success, published by Stein and Day, a publisher specializing in literary best sellers. It was shepherded into print by her friend and Harper’s Bazaar editor, Alice S. Morris, who published excerpts. As with all of her books she went through an agonizing process of rejection before placing it. And even more so than her other books she labored over its composition for many, many years, even publishing another novel, started later, first (The Choir Invisible, 1958). In Botteghe Oscuro (the Wikipedia article is here)…(The Sun and the Colonel’s Button. Botteghe Oscure 12, Fall 1953, 255-72.) she published the first chapter, but written in the third person. She writes of having a breakthrough and discovering the voice of Hauser, probably in 1953 or 1954. She worked on the book throughout the decade, abandoning it and returning to it. By the time she moved back to New York City in 1958 it was substantially complete. Here are some reviews, by her friend Harriet Zinnes (whom she taught with at Queens College, a poet), from the Saturday Review, a publication she reviewed for in the early forties,and Guy Davenport in The National Review:

Marianne Hauser. Prince Ishmael. New York. Stein & Day. 1963. 316 pages. $5.95. Although this is on the surface a historical novel about a young man who makes a strange appearance at the Nuremberg gates in the early years of the nineteenth century, the novel in texture and meaning is strikingly contemporary. Caspar Hauser, found in the dark, and completely dark about himself, symbolizes that terrible search for identity which becomes in our time and in this novel the search for the spiritual father. The whole mystery of the self and its inevitable confusion, the whole mystery of the acts of the self that turn present into past and leave no future, that make suspect and victim interchangeable and eccentrically identical (“Had the whale swallowed Jonah? Had Jonah swallowed the whale?”)-these are the mysteries that are embodied in that angelic, naive, corrupting and corruptible youth Caspar Hauser. Marianne Hauser describes her narrative of today’s everyman in a style rich in suggestiveness and poetic in expression-and finally, religious in its assertion of the triumph of suffering man: “You call me what you will, angel or liar, I may yet live forever, mark my word.”

Harriet Zinnes Queens College

Books Abroad, Vol. 39, No. 1 (Winter, 1965), p. 88

Caspar Hauser was one of the most enigmatic figures of the nineteenth century. A semisavage and inarticulate young man, he first appeared in Nuremberg in 1828, spent five tortured years under the tutelage of various guardians, and then met an end as mysterious as his beginnings. Was he the disinherited scion of a ruling house, a charlatan, a madman, or perhaps all of these? Speculation ran high, and has continued to this day. Writers in Germany, France, and England were fascinated by the dark fate of the foundling, and the interpretations vary from the calme orphelin of Verlaine’s great poem to the saintly scapegoat of slothfulness of heart presented by the German novelist Jakob Wassermann.

In her new novel, Prince Ishmael (Stein & Day, $5.95), part of which appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Marianne Hauser vividly recreates the brutish ambience of Caspar’s short life. Narrating the boy’s story from his point of view, she displays a keenness of psychological insight whose impact is immediate. However, her sympathetic evocation of the archetypal outcast does not merely present the “facts” of the case, but bestows upon the hero an aura of almost mythical grandeur. Caspar’s emergence from the womb of night, his mirror calligraphy, and his helpless groping in the labyrinth of his own mind symbolize the existential plight of man in a bewildering universe.

Miss Hauser’s probing analysis of character unfortunately is not matched by an equally acute sense of style, and now and then her prose verges on the sentimental, especially in passages of lyrically exalted nature mysticism. More successful is the surrealistic portrayal of the agony of a lost soul, oscillating between reality and appearance. Though Prince Ishmael implicitly criticizes the materialistic goals of a mechanized civilization, it never becomes harsh or aggressively polemic.

To make her plea for the confused and the oppressed of this earth, Miss Hauser prefers the more gracious art of symbolism. She thus recaptures the fervor with which the last century hailed Caspar Hauser, victim of Nuremberg, as “The Child of Europe,” and has erected another monument to his memory.

Saintly Scapegoat, JOSEPH P. BAUKE. Saturday Review, September 7, 1963 pp24, 35

The Multiple Man, by Guy Davenport, The National Review, October 8, 1963, Pp. 310-313.: